Last Updated on September 8, 2023

The term derivative relates to something which “has a value deriving from an underlying variable asset.” Financial derivatives can be used in hedge scenarios or as a means of taking a speculative position on a particular asset. Due to the structure of a financial derivative, a relatively small movement in the underlying asset’s value can significantly impact the value of the derivative. The cause of this disparity is leverage, which is just one of the many characteristics derivatives have. What else makes financial derivatives unique? Let’s dive in and find out.

What are Derivatives in Trading?

It often surprises people when they ask “what are derivatives” and find out that their use mainly relates to risk hedging. Many people automatically associate derivatives more closely with speculative investors than those looking to protect/cover existing positions. Even those buying derivatives without any asset to cover can create strategies that limit the downside but maximize the upside. We should not look at them as an out-and-out gamble.

It is also commonplace for investors to use derivatives to protect and maintain the value of an existing portfolio. Then there’s the commercial element for those looking to acquire/sell commodities as part of their business operations. The opportunity to secure supply well before the delivery date is essential when planning at a predetermined price.

Derivative Exchanges and Over the Counter Derivatives

There are two main ways to acquire derivatives: via recognized exchanges and over-the-counter arrangements.

Derivative exchanges

Derivatives traded on open exchanges are marked-to-market each day. This process prompts adjustments in margin calls/collateral and reduces the risk of default. This low risk of default can create colossal interest, and their deep-seated liquidity reflects it. Most large-scale investors consider them a must-have. Exchanges with high levels of liquidity create an environment for highly efficient pricing, helping to avoid pricing anomalies and arbitrage positions.

It is also important to note that you can buy and sell exchange-traded derivatives as often as you want before expiry. All trades go through a clearinghouse which ensures efficient and prompt settlement.

Over the counter derivatives

Often referred to as OTC derivatives, these are transactions negotiated and completed away from a recognized market. As we cover the different derivative exchanges, you will notice many have standard contract sizes with no room for negotiation. The two parties can directly negotiate the arrangement’s price, volume, and duration with OTC derivatives. The commercial world appreciates this greater flexibility more than retail traders. However, it comes at a cost. Typically, you cannot trade OTC derivatives with other parties after the initial setup. Even in the cases where it’s possible, it can sometimes be challenging to achieve a fair price.

While derivative exchanges will adjust margin calls and cover daily, OTC derivatives tend to be cash on delivery. Consequently, you may not become aware of any issues with the other party until the arrangement needs to be settled. In reality, there are enormous financial and commercial institutions involved in the OTC derivatives market. Therefore, it is possible to reduce the chances of default by trading via recognized firms with a strong reputation.

Common Types of Derivatives

When looking at derivatives, it is helpful to look at these on two different levels. Firstly we have the type of derivatives, and then we have the assets on which these derivatives are based. The most common types of derivatives are:

- Forwards

- Futures

- Options

- Swaps

The most common types of underlying assets for derivatives are:

- Commodities

- Stocks

- Bonds

- Interest rates

- Currencies

While you can trade derivatives on an array of different assets, each derivative will have many common factors, which include:

- Asset

- Price

- Quantity

- Delivery date

- Margin (where applicable)

Some derivatives are traded in isolation and others as bundles, but the core information is still the same. When you purchase or sell a derivative, unless the position is closed before expiry, you are generally committed to either purchasing or delivering an asset.

When writing a derivative (going short), you will only be expected to provide collateral to cover an element of the full financial exposure; this is referred to as margin. Consequently, it is possible to create significant leverage on a relatively small investment. The result is an environment in which you may incur substantial losses or make substantial gains. Be careful!

Futures Contracts

Whether looking at oil futures, stock futures, or E-mini S&P 500 futures, the concept is the same:

- A buyer is obliged to buy an underlying asset at a predetermined price and date in the future

- A seller is obliged to deliver an underlying asset at a predetermined price and date in the future

Many people confuse futures contracts and forward contracts because they are pretty similar. The main difference is the way they are traded and that futures contracts are standardized for quantity. Futures contracts are “marked-to-market” daily which means that margin requirements are continuously adjusted. The required margin call can increase or decrease across the duration of a futures contract.

As futures margin calls are monitored closely, this significantly reduces the risk of default. Consequently, this facilitates the often heavy trading of futures contracts like indices, currencies, and commodities (oil is a popular market!).

If we look worldwide, the ten largest futures exchanges are as follows:

- CME Group (Chicago Mercantile Exchange), US

- National Stock Exchange of India, India

- B3, Brazil

- Intercontinental Exchange, US

- CBOE Holdings, US

- Eurex, Europe

- NASDAQ, US, and Europe

- Moscow Exchange, Russia

- Korea Exchange, South Korea

- Shanghai Futures Exchange, China

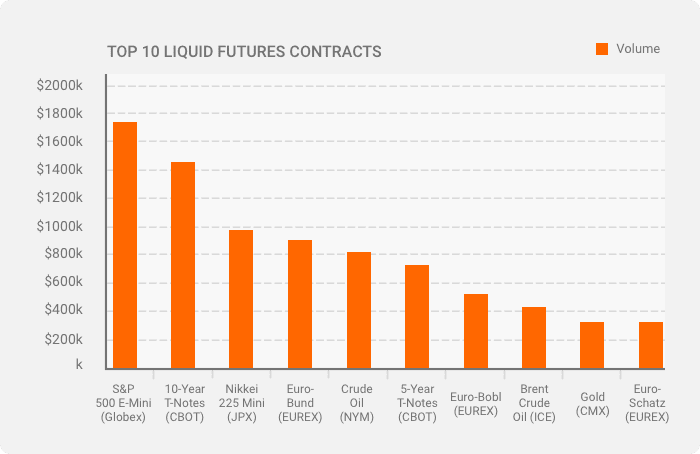

It is fair to say that the US has a solid foothold in the futures sector across a wide range of different assets. The following graph shows the top 10 liquid futures contracts traded around the world:

The History of Futures Trading

Many people believe that futures trading is a relatively new phenomenon, but this is not the case. The first recognized futures trading exchange can be traced back to Japan in the 1730s. The asset was created solely for trading rice futures which were a massive part of the regional economy. There is some dispute regarding the London Metal Exchange (LME), officially established in 1877. However, evidence suggests that commodity futures began trading in England as early as the 16th century.

The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was created in 1848 after a notable investment in the US transport network. This new infrastructure connected farmers with cities such as New York, Chicago, etc., and was the precursor to the thriving futures market we see today. The ability to deliver agricultural commodities to the major cities of the US-led to an increase in demand and improvement in prices.

Forward Contracts

As we touched on above, there is a tendency for people to confuse futures contracts and forward contracts, often seeing them as the same. It is still possible to take out forward contracts on currencies, market indices, and individual stocks, but they tend to be popular with commodities, particularly agricultural commodities.

On the surface, futures and forward contracts may appear very similar, but there are significant differences.

No central market

A forward contract is an agreement between two parties customized to consider a commodity, amount, price, and delivery date. You will see forward contracts as over-the-counter (OTC) instruments with no centralized clearinghouse, which we see with futures contracts.

No margin adjustments

Regulated futures markets operate on the clearinghouse principle, effectively taking the collective risk of default. Forward contracts are unregulated, and therefore the terms and conditions are stipulated by the two parties. As there is no central clearinghouse with forward contracts, the risk of default is more significant. While futures contract margins are adjusted daily, with forward contracts, there is no such adjustment. Settlement is simply on the agreed delivery date.

Flexibility

While the risk of default, in theory, is higher with forward contracts compared to futures contracts, forward contracts have greater flexibility. Rather than trading nominal contract sizes, as you see with futures, a forward contract will cover an agreed amount of a particular asset.

Risk of default

As we touched on above, the risk of default is significantly higher with a forward contract than a market traded futures contract. So how do the large financial institutions get around this?

Simple, because these are unregulated transactions, it comes down to the quality of the parties with whom you are dealing. No trade is ever risk-free, but arranging forward contracts with a reputable firm gives you a degree of security. After all, why would they risk their reputation by defaulting on a forward contract?

When looking below the surface of the worldwide investment sector, you will see that one of the more valuable commodities is reputation. Quite simply, nobody will deal with you if you have a bad reputation in the market.

Options

Traded options are an exciting means of hedging or taking a speculative position on a particular asset. Unlike futures contracts and forward contracts, where the initial value is based on the real-time price of the asset, it is slightly different for options. They have numerous in-the-money, at-the-money, and out-of-the-money strike prices, with a range of expiry dates.

Before we look at this in more detail, it would be helpful to list the variables of a traded option contract:

- Underlying asset

- Strike price

- Option price

- Quantity

- Expiry date

There are two different types of traded options:

- Call options, which give the buyer the right but not the obligation to acquire an asset at a predetermined price and date

- Put options, which provide the buyer the right but not the obligation to sell an asset at a predetermined price and date

The majority of traded options contracts are closed down before their expiry date, creating welcome liquidity. You will find that futures contracts and traded options contracts are often available on the same exchanges. Therefore, it will be no surprise to learn that the six largest international option exchanges are as follows:

- Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE)

- NYSE Arca

- International Securities Exchange

- Boston Options Exchange

- Eurex Exchange

- Montréal Stock Exchange

Traded options are predominantly used to hedge or take positions in individual stocks and international indices. Popular/volatile stocks and indices attract the lion’s share of traded option activity, with essential liquidity. While these exchanges are open to individuals and investment companies, they are dominated by large financial institutions, often taking huge positions. As a consequence, they tend to stick to the more liquid markets.

Assets Traded as Options

For example, you can buy and sell traded options in the following US indices:

- S&P 500

- Russell 2000

- NASDAQ 100

- Dow Jones Industrial Average

- CBOE Volatility Index

Due to the underlying liquidity when buying and selling shares, you will also be able to trade options on a range of international companies. The more common stock options traded in the US include the likes of:

- Apple

- Tesla

- Amazon

- Bank of America

- AMC Entertainment Holdings

Trade options allow investors to take out speculative/hedging positions and draw up several strategies. Some of the more common techniques include:

- Covered call

- Protective put

- Bull spread

- Bear spread

- Protective collar

- Long straddle

- Long strangle

- Butterfly spread

Due to the array of strike prices, expiry dates, and put/call options, you can create positions that maximize the upside but limit the downside. It is essential to plan such strategies and take advice where applicable.

Swaps

While many investors will have heard of swaps, the more common type of derivative with interest rate swaps, you may be unsure exactly how they work. The easiest way to describe a swap is a derivative instrument that exchanges two parties’ cash flow/liabilities. The rate on one side of the transaction is fixed while the other is variable, introducing a degree of risk.

As with all derivatives, there are several standard variables such as:

- Asset

- Amount (principal)

- Duration

- Base price (interest rate)

- Premium

In this instance, we have adapted the list to reflect the variables associated with an interest rate swap, at the same time, not the only type of swap transaction. The customized interest rate swap market is vast. However, the majority of transactions are arranged off-market via over-the-counter contracts.

Unlike futures contracts, where there are clearly defined contract sizes, an interest rate swap would be customized to accommodate both parties. As the principal involved does not change hands, just the cash flow/liability, the financial risk is reduced. While there is always an element of default risk with any investment transaction, part of the risk/reward ratio, this market is dominated by businesses/large financial institutions. As always, the risk of default is reflected in the quality of the parties you transact with.

To understand the mechanics, we have put together an example of an interest rate swap in the next section. There are other types of swaps which include:

- Currency swaps

- Commodity swaps

- Credit default swaps

While swap derivatives can create speculative exposure, they tend to be seen as more of a hedging tool. Most swap derivatives are arranged and traded off-market, reducing the traditional protections available with exchange-based trading.

Real World Derivative Examples

This section has put together some real-world derivative examples, covering their role in commercial and investment markets.

Example of a futures contract

The S&P 500 index is the most heavily traded futures contract on the mainstream market. The main S&P 500 futures contract is worth $250 per point, which at the current level of 4374 equates to $1,093,500 per contract. Even using the lower 3% margin often quoted, the minimum margin requirement would still be approaching $33,000. Thankfully, as the S&P 500 index continued to soar, we saw the creation of the E-mini S&P 500 futures contract, which is worth $50 per point. An example trade would be as follows:

- S&P 500 index: 4374

- One contract: $50 x 4374 = $218,700

- Example margin call: 3% x $218,700 = $6561

- If the index were to rise to 4400, the situation would be as follows:

- Value: $50 x 4400 = $220,000

- Cost: $218,700

- Profit: $1300

Based on the total value of the futures contract, this equates to a return of just 0.6%. However, in this example, the margin payment was just $6561, which equates to a profit of 19.8%. This number is the impact of leverage and that you only pay a tiny element of the overall contract value, the margin. However, if the index had fallen to 4348, this would have created a loss of $1300.

Example of a forward contract

Forward contracts are commonplace when buying and selling agricultural commodities such as corn bushels. While many forward contracts are agreed on off-market, known as over-the-counter, it is possible to trade on recognized exchanges. In this instance, we will work on 1000 corn bushels per contract for $5.29 per bushel.

The typical forward contract would look like this:

- Purchase: 100 contracts

- Delivery: December 2021

- Transaction value: $5.29 x 100,000 = $529,000

- Example margin: 10% x $529,000 = $52,900

This forward contract places an obligation on the buyer to acquire 100,000 corn bushels for $5.29 per bushel. It matters not whether the price falls or rises between purchase and delivery date. If the price were to fall, then this would create an effective loss. If the price were to rise, then there would be a paper profit.

The primary purpose of forward contracts in the agricultural world is simply to secure the supply of, in this instance, corn bushels. It allows companies to calculate their costs and profit margin with a degree of certainty, in the knowledge that they have secured a supply of corn bushels.

Example of a traded option

You can create many different strategies using traded options, calls, and puts, but we will look at a simple call option in this instance.

Call option

A call option gives the buyer the opportunity, but not the obligation, to acquire a particular asset at a predetermined price and date. Let’s say, for example, you were optimistic about the Tesla share price and wanted to purchase a call option.

Here is a snapshot of real-time Tesla call option prices, which expire on 20 August 2021:

- Tesla share price: $653

- Traded option strike price: $700

- Expiry date: August 2021

- Option price: $24.95

- Shares per contract: 100

- Number of contracts: 10

- Cost: 10 x 100 x $24.95 = $24,950

If we acquired a traded option with a strike price of $700, this would give us the option, but not the obligation, to buy Tesla shares at $700 on 20 August 2021. When the strike price is higher than the share price, it becomes what we call an out-of-the-money option. So basically, the price of the traded option relates to time value – there is no intrinsic value.

We will look at a couple of expiry scenarios:

- Stock price on expiry: $700

- Option price: $0

- Option value: $0

- Net loss: $24,950

- Stock price on expiry: $750

- Option price: $50

- Option value: 10 x 100 x $50 = $50,000

- Net profit: $50,000 – $24,950 = $25,050

In the first example, there is a 100% loss as the option expired worthless. In the second example, there is a profit of just over 100% on a 14.8% swing in the share price. These numbers perfectly reflect the idea of leverage and a successful out-of-the-money call option.

Example of a swap

Let’s say Company A issues a $10 million loan note with a five-year duration, paying an annual interest rate of 1.5% over LIBOR. The company is concerned that interest rates may rise over the five years, potentially increasing the interest they will need to pay to investors. Here is a summary of the scenario:

- Loan note: $10 million

- Duration: Five years

- Interest rate: LIBOR + 1.5% = 4%

- Annual interest: $400,000

To secure a fixed rate for the duration of the loan note, Company A carried out an interest rate swap. The company found a third party, Company B, willing to cover the annual interest charge (currently 4%) in exchange for a premium of 5% per annum. So, Company A now has an obligation to pay $500,000 a year to Company B, which will, in turn, cover the payment of interest to investors.

If the LIBOR rate increased by 2%, this would increase the annual interest payable to 6% or $600,000 per annum. However, if the LIBOR rate fell by 2%, this would reduce the annual interest payable to 2% or $200,000 a year. In effect, Company A and Company B exchanged cash flow liabilities. Company A will pay $500,000 a year in fixed premiums while Company B is exposed to a variable rate. Any interest rate over 5% per annum equates to a loss for Company B. Meanwhile, anything under 5% per annum equates to a profit.

In this situation, Company B must be confident that rates will not rise significantly, while Company A is simply securing a fixed rate. Initially, Company A pays a $100,000 a year premium, over and above the initial 4% rate. This premium is the cost of securing a fixed rate which will help with cash flow and budgeting.

The Advantages of Derivatives

There are many advantages when using derivatives such as:

- Fixed prices

- Speculative leverage

- Diversification

- Hedge against risk

- Security of supply

- Firm delivery dates

- Reduced risk of default on recognized exchanges

It is also possible to create strategies using multiple derivatives to maximize your upside while minimizing your downside.

Risks Associated with Derivatives

There are also some potential disadvantages when using derivatives which include:

- Potential counterparty default (OTC transactions)

- Derivative prices are sensitive to many outside factors

- Margin calls

- Derivatives can be difficult to value

- Some derivatives are non-tradable

- Potential open-ended losses

In some cases, taking out a covered derivative position to secure the value of an existing asset can appear expensive. In this scenario, you should think of the cost as you would about an insurance premium.

Final thoughts

Whether you are looking to protect an existing position or facilitate a speculative investment, numerous options are available. It is essential to recognize the most appropriate type of derivative for your situation. There are four main types of derivatives we can use in tandem with a vast range of assets. Some have fixed contracts, while others can be customized with direct negotiation between both parties.

The degree of available leverage available attracts many traders to derivatives, especially with more speculative positions, but this works both ways if the investment goes the wrong way. We hope we have answered the question, what are derivatives. Be careful!