Last Updated on February 8, 2019

The latest economic news coming out of Peking has been somewhat pessimistic as recent headlines mention lower economic growth and declining foreign trade activity. Based on macroeconomic indicators it’s become clear that the trade dispute between the world’s two largest economies is taking a toll on China as well.

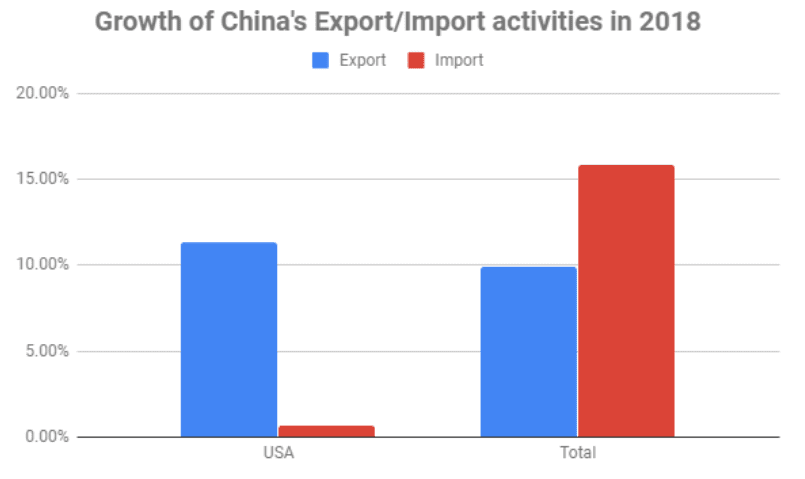

The tariffs proposed and enacted by Donald Trump were allegedly introduced to fix the USA’s trade deficit in general, however, it’s no secret that China was their main target. Although the gradual addition of these tariffs immediately made markets nervous, macroeconomic indicators barely showed any actual changes up until the last quarter of 2018. Now that the data on the final months of last year has come out, China’s economic outlook is slowly beginning to shift for the worse. We already know for a fact that the US tariffs in question did not improve the country’s trade balance with China in 2018. The latter has managed to increase their trade surplus with the US by 17% compared to the previous year, totaling at 323 billion dollars. At fist glance this severe trade deficit could be interpreted as a policy failure by Washington, since China’s export increased by 11.3% despite the tariffs while their import of US products only rose by a negligible 0.7%. These figures become even more impressive when taking into account that on the whole, China’s trade balance has been stuck in a declining trend during 2018. The country’s total exports and imports grew by 9.9% and 15.8% respectively, meaning their imports expanded at a significantly faster rate than their exports.

The above chart illustrates that China’s retaliatory measures against the US last year were fundamentally effective. One of the main reasons for the success of China’s measures was the rising relative purchasing power of the US dollar putting the States at a disadvantage in export activity. Many analysts have noted that US companies, in order to avoid the tariffs, chose to advanced their orders and stockpiled Chinese products before the tariffs went into effect. This suggests the increase in China’s trade surplus could simply be a case of the candle burning brightest before going out and the economic reports seem to confirm it.

Looking at December of 2018, both China’s exports and imports dropped compared to the same period of the previous year. Exports declined by 4.4% and imports by 7.6% compared to December of 2017. These numbers showcase a weakening demand in both foreign and domestic markets.

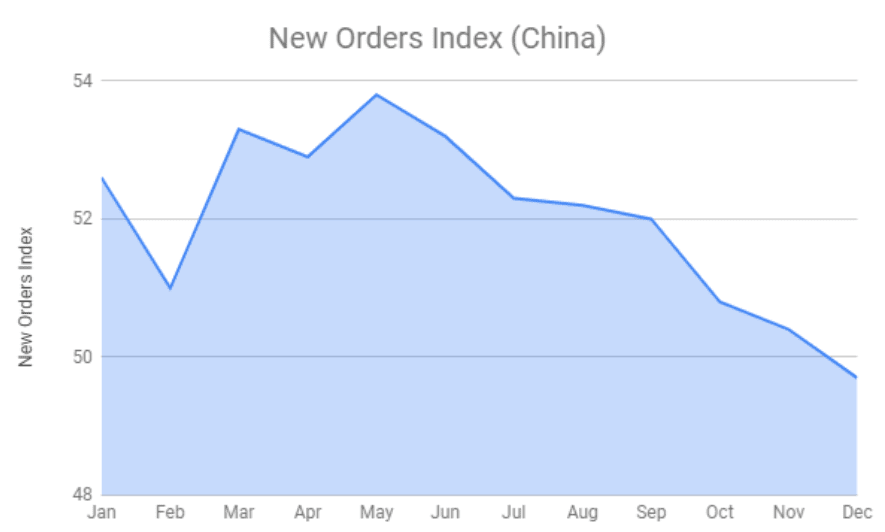

The New Orders Index strongly correlates with the changes in import and export figures. This index has been on a distinct downwards trajectory ever since it’s May high. The declining demand for Chinese products has made their manufacturers cautious in planning their own acquisition. Lower Chinese imports have also disadvantaged numerous other Asian countries. The slowing Chinese growth, as shown by the declining new orders and export activity, could potentially trigger a recession spreading across other Asian countries in a domino effect. The 7% drop in China’s imports can mainly be attributed to the reduced demand for raw materials used in production. Their import of coal and refined copper dropped by 50% and 11.3% respectively. The other notable import that fell was soybeans by 40% and it can fully be attributed to China halting US soybean imports.

Based on the data is seems that after half a year China’s initial strong resistance to the tariffs is starting to weaken and their GDP growth may even end up below 6%. Such a low growth rate would not be enough to support the economic growth of countries dependent on exports to China so they’ll actually be the first to feel the effects of the US tariffs. The most affected would be Australia and Russia who’ve supplied a large part of China’s resource needs in the past. The Peking government has attempted to reduce the negative effects with tax cuts and increased government spending, however these measures need time to show any results. At this point it’s entirely possible that in 2019 we may end up seeing China’s economic growth numbers drop below even what they were during the 2008 crisis.